Modern Drummer Magazine, August, 1985

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Simon Goodwin

TAKING an extremely simplistic view of the development of the percussion instruments that make up our modern drumset, we think in terms of the cymbals originating in Turkey or China, the tom-toms in Africa, and the bass and snare drums, as we know them today, developing in Europe. These were the instruments of military bands and symphony orchestras, and nowhere were these movements stronger than in Germany. It was the German classical composers writing for bigger and better percussion sections tions-whose members, in turn, demanded bigger and better drums-who were largely responsible for the increased use of drums outside a military context. There is, therefore, a tradition of drummaking in Germany that goes back a very long way.

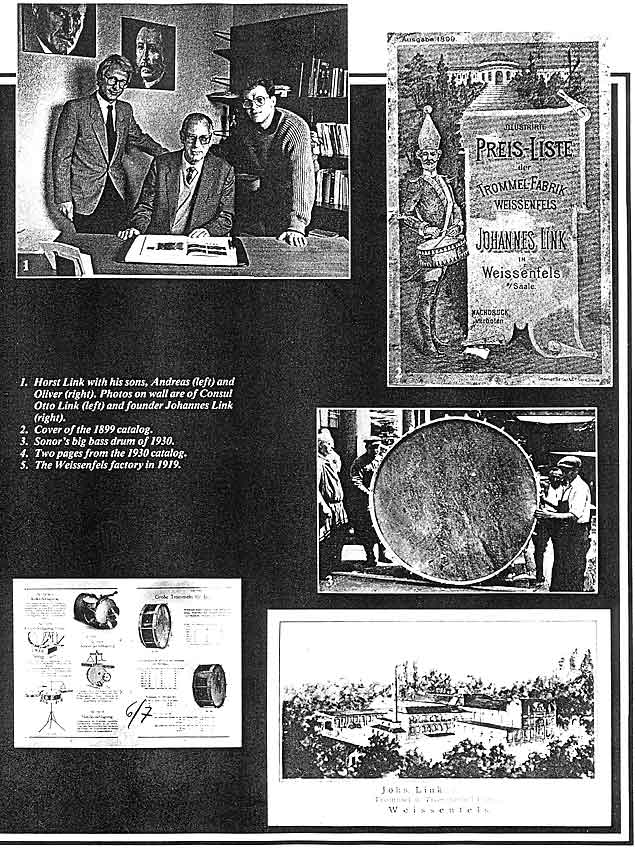

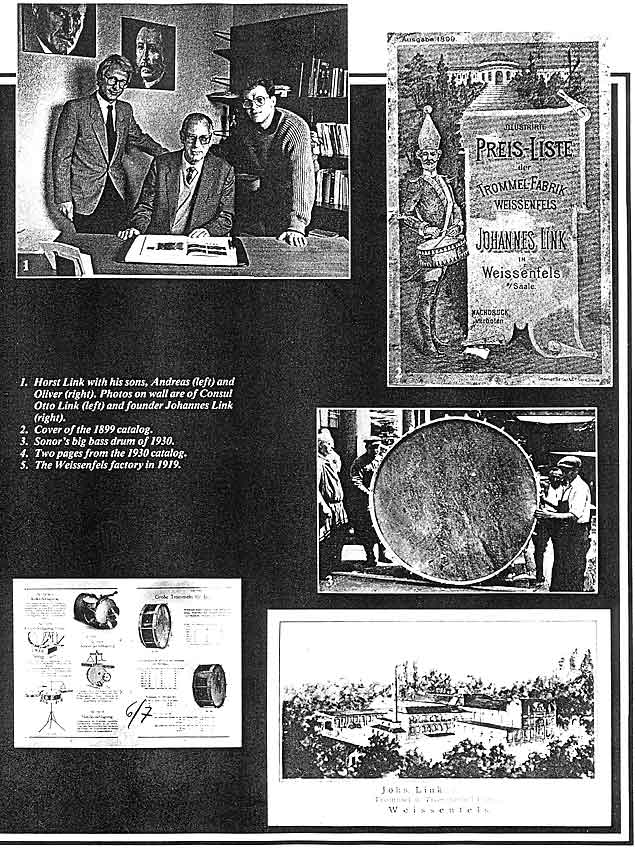

The country's leading drum manufacturer today is Sonor, a company that has been run by the same family for 110 years. It was founded in 1875 by Johannes Link, who had previously been a wood turner and tanner. Johannes Link started by producing military drums and drumheads, but within the next 25 years, his factory at Weissenfels expanded in size and in the range of instruments that it produced, so that by 1900, the company was manufacturing a full range of top-quality percussion instruments. The 1899 catalog shows items like pedal timps, a snare drum with independent tuning for each head, and a snare drum stand-all of which we take for granted today, but which were up-to-theminute new ideas then.

Johannes Link died in 1914 and was succeeded by his son Otto The company continued to prosper in Weissenfels, under Otto Link's guidance, for the next 36 years. Strangely enough, however, it was another, quite separate, career he had that indirectly made the company's present situation possible. Otto Link, as well as being an industrialist, was Honorary Consul to Sweden. In 1946 Otto's son, Horst, decided to move out of the Russian-controlled sector of Germany, because the Russians were arresting ex-officers and imprisoning them in Eastern Siberia, "which I wouldn't have liked," he now adds dryly. He moved into the British sector, and rather than having anything to fear from the British Army, he was actually able to buy a disused barrack hut from them, which was to become the first Sonor factory in West Germany. So it was that Horst Link started doing business in the company's present location of Aue in Westphalia. He started by only making drumheads. The Sonor factory at Weissenfels was now in East Germany, and so were Horst's mother and father.

When the border was closed in 1950, it was clearly only going to be a matter of time before the original Sonor factory would be expropriated and taken over by the State. Preparations were made for Otto Link and his wife to escape to the West, but nothing was done until the police were sent to arrest Otto at his home. It was the family's maid who saved Otto, by saying that he had already left for the factory. Otto, meanwhile, climbed through a window at the back of the house and made good his escape. Frau Link was able to follow her husband a few months later, but not without having some adventures of her own. She had to pretend to be visiting a cemetery near the border, where some friends were standing by with a fast car to whisk her away.

So father and son were reunited in the West, but at this stage, they had nothing except Horst's barrack-room drumskin plant. They needed land on which to build, skilled labor, and capital. The local community in Aue welcomed them; the community was interested in the possibility of encouraging fresh industry in the area and it was relatively easy for the Links to obtain the land they needed. The capital was to come from an unexpected quarter. A Swedish noblewoman, the Princess of Sayn-Wittgenstein, lived and owned land (and still does) near Aue. The then King of Sweden liked and respected Otto Link since his period as Consul in that country. Hearing about Otto's escape to the West, the King contacted the Princess and suggested that she might be able to help his old friend save his family business. So the Princess became a partner in the company, and remained so until the late '70s.

Building up the company again from nothing was hard work. The family managed to keep the "Sonor" trademark, which had been registered by them in 1907, but they had very little to show for two generations of successfully building up the business in Weissenfels. (Owned by the East German government, the factory is still producing percussion instruments under the name of Tacton.) Even the experience that had been developed during this time was mostly lost. Two craftsmen from Weissenfels managed to escape to the West and join Sonor in Aue, but otherwise they had to start training new people in an area where, previously, there had not been any manufacturing industry, only agriculture.

It was another ten years before they had sufficient skilled craftspeople to develop the company in the way they wanted, but sadly, halfway through this period, Otto Link died.

Horst Link intimates that his father's death came as a double blow to him, because when it occurred, he didn't feel ready to take over the reins of the company, which was struggling to reestablish itself. But as so often happens in these situations, the son had no choice. Under his leadership, Sonor slowly and successfully grew until, in 1975 (100 years after his grandfather had founded the company), Horst Link had achieved what he had set out to do 20 years before.

There is now a fourth generation involved in the family firm. Andreas Link is currently understudying his father and acting as his assistant. I suggested that this makes Andreas the Vice-President. This amused him, and he said that if Modern Drummer wanted to give him this title, he would accept it. The younger son, Oliver, is a keen drummer and artist; his talents are put to good use in his job as Advertising and Promotion Manager. At 25, Oliver is very aware of, and interested in, today's music scene. The company's image is in his capable hands; he has some first-class products to promote, but they have to be presented to the drumming community in the right way. Oliver Link wrote and designed the recent Sonor catalog, The Drummer's Drum. I think anybody who has seen it will agree that it is quite an achievement.

|

|

|

|

|

While Horst Link is head of the drum division of Sonor, his wife Elizabeth runs the side of the company that produces the excellent educational range of instruments. This is no small sideline, because 50% of the company's business is represented here. They started making the educational instruments in 1950, at the same time as they started manufacturing drumkits in Aue. It was with the educational instruments that Sonor first started to make inroads into the American market in 1960. Part of the success of the range, apart from its undoubted quality, must be put down to the fact that Sonor makes educational instruments to supply the needs of a particular system of music teaching. The Orff system (pioneered by professor Carl Orff, the composer of Carmina Burana) calls for a wide range of instruments that can be used constructively by children of all ages. Elizabeth Link not only heads this side of the company, but she also runs IGMF, an "international society for music in education," and organizes courses that she sometimes also teaches. For many years, Sonor has been concentrating on drumkits and Orff-system instruments. The company hasn't been making marching drums or professional orchestral instruments, but this is changing. It has recently started making marching drums again, and the rest is likely to follow.

It is Sonor's range of drumkits and the company's dedicated, but possibly slightly controversial, approach to drum design that will be of most interest to readers of Modern Drummer. Sonor makes five different ranges of drums. They are, starting at the top: Signature (Heavy and Light), Sonorlite, Phonic, Phonic Plus, and Performer. For the purposes of instant recognition (the other differences will be dealt with as we go along), the Signature series has the gold badge, the Sonorlite series has the black badge, the Phonic series and Phonic Plus series have the silver badge, and the Performer series has a silver badge with a yellow flash below the logo. There would be a tendency for any potential customer to line up, in his or her mind, this range of drumkits alongside the products of any other company that makes a range of four or more different-quality kits and start thinking in terms of equivalents. Sorry, but this just can't be done! In Europe, Sonor's Phonic/Phonic Plus range (the third one down!), which the company describes as the "foundation" of their program, is slightly more expensive than most British, American, or Japanese kits aimed at the professional end of the market. This means that they have two ranges that go beyond this level. The Performer is cheaper, but it is hardly a budget kit, being priced somewhere between anybody else's professional and mid-range kits. In America, Sonor drums are even more expensive, so the ratio becomes even more extreme. You could almost say that Sonor starts at the point where other drum companies leave off. Why?

I had a round-table discussion with Horst, Andreas, and Oliver Link, and also Steve Gardner, Director of Sonor UK, the British marketing operation, who gave the salesman's viewpoint. Horst Link explained their approach to quality in manufacturing. "We don't try to compete with the big manufacturers, like the Japanese, in terms of quantity; we compete with quality. We maintain a quality that is better and has a higher standard than anything else. Our drums are expensivethere's no doubt about that-but we have no intention of making compromises. We will never sacrifice quality for a cheaper price. You might suggest that, if we brought the price down, we could sell more drums, but we can't bring the price down and maintain the quality. We would rather sell fewer drums than compromise in this way. The idea of the Signature series was for us to come out with a drumkit that couldn't be made better. It should really be the best! Forget the price. Even if it was so expensive that nobody could afford it, we just wanted to build the best. We never intended it as a big seller, but as it turned out, it exceeded all our expectations. For the home market, we sell more Phonic, Phonic Plus, and Performer kits, but in other countries where we are 'in the lions' den' and the competition is greater, like America and Japan, the Signature is the best-selling kit in our whole range. There is also the fact that we sell more kits in America than anywhere else, so you can see how successful it has become."

The Signature (Heavy) series shells are made of 12-ply beech and are 12mm (nearly 1/2") thick. The natural-wood finishes (which are the only ones in Signature) are African bubinga and Indonesian Makassar ebony. The bass drums have twin, upright, internal muffling strips of lambs wool, which can be moved (not stretched) against the batter head by means of an external control. The mechanism is guaranteed not to rattle when the mufflers are in the "off" position. There is a choice of wood- or metal-shell snare drums 8" or 61/2" deep, with parallel-action snares. The adjustment mechanism is guaranteed not to wear or to go out of alignment, and Steve Gardner estimates that you can go for at least five years without needing to make any adjustments. The rack toms in the Signature series are all "power" sizes, being as deep as they are wide, and there is an interesting choice of floor toms: the 14" is 16" deep, the 15" is 17" deep, the 16" is 18" deep, and the 18" is 19" deep. The Signature series is also available with lighter shells made from birch; these are still 12 ply but the thickness is down to a more usual 7mm. All Signature drums are fitted with "Snap Locks" on the nut boxes: The thread housing (into which the tension bolt is screwed) has a small section cut out on one side, a clamping ring around the outside of the housing comes into contact with the thread of the tension bolt at this point, and as the bolt is slightly flattened on two sides, the clamp locks the bolt in position at every half turn. It is easy to turn it with a drum key, but it will not slip accidentally during playing, allowing the drum to detune.

Like the lighter Signature drums, the Sonorlile series has bass drums and snare drums made of 12-ply birch with 7mm shells, but the tom-toms are 9 ply and 6mm. The available finishes are Scandinavian birch (natural wood), creme lacquer, and onyx lacquer. The tom-toms are one or two inches shallower than their Signature counterparts, and the choice of snare drums includes ones with direct-pull snare levers. It is actually when we come to the Phonic that we are looking at something like the average, traditional, top-quality, professional drumkit. The Phonic has the non-power sizes, like 8x 12 and 9x 13. The Phonic Plus series consists of Phonic drums in "power" sizes. The shells are 9ply beech and 9mm thick with a wood finish, 10mm with a plastic covering. Phonic and Phonic Plus are available in red mahogany (natural wood), or black, white, or red plastic. There is also a new Phonic Plus "Hi-Tec" kit with grey shells, and black fittings and hardware. The Performer kits are only available with plastic finishes and traditional drum sizes. They have 6-ply beech shells that are 7mm thick.

To explain why Sonor favors heavier, more solid drumshells, even in its lighter models, it is easiest to quote Oliver Linknot from anything that was said during our interview, but from what he says in The Drummer's Drum. Research has been carried out at the German Federal Institute of Physics into "how the materials, form and size of a drum interrelate and affect the sound quality of the instrument." It was found that the drumshell doesn't contribute to the sound of the drums. It should be passive. It is the volume of air contained within the shell that reacts with the vibration of the heads to produce the sound. Oliver's conclusions are as follows: "The shell must not vibrate, in order not to deprive vibration energy of the drumhead by its own vibration. The shell must have a high flectional resistance; the higher the flectional resistance, the less chance of the shell producing its own vibrations. The shell must have a great mass, thus making the decay of the drum sound to a large extent independent from the way it is fixed to holders or stands. Furthermore it favors an efficient projection of the fundamental tone." So a drumshell shouldn't vibrate, but once free of vibrations, the thickness of the shell can still affect the sound of the drum. According to Oliver, "The basic frequency will be more muffled when the shell has a thin wall, so that the upper frequencies emerge. The sound seems to be more brilliant and sustaining. Shells with thicker walls and equipped with the same type of heads have the same spectrum of overtones as thin shells. However, the projection of the fundamental tone is better. The sound seems softer and fuller."

According to Horst Link, "The sound of a drum comes only from the heads; the shell only gives the volume of the resonance space. The shell shouldn't take away any vibrations from the reaction of the heads to the space inside the shell. If the shell vibrates, it takes power from this process. The sound of a drum will improve as you put more on a shell-even with weights; you could cover a shell in concrete; it cannot be heavy enough for the ideal projection of the head sound. This is with regard to the basic tone of the head. But we do make tighter drums. This is because the overtones can be an important consideration in the overall impression of the sound. Some people want to hear some overtones, so with the Sonorlite, you get a reduced basic tone with more overtones. It is a livelier, more colorful sound."

Steve Gardner said, "The whole idea of vibrating shells was in somebody's mind. Research wasn't done to see whether a vibrating shell really did give you a better sound. Even this company used to advertise shells as being 'full vibrating,' and it wasn't until somebody said to them 'Hang on a minute. It's only when you stop the shells from vibrating that you put the energy into the head,' that they changed. If you have a vibrating shell, you are taking energy away from the heads, so you lose volume-and more importantly, you lose tunability. You lose the potential of tuning a certain size of drum to its optimum highest pitch or its optimum lowest pitch; you are stuck with this thing that most drums of the '60s had, where you had a set sound that you couldn't get away from. I think that a lot of companies have been having trouble with their power toms. Again, it's all in the mind. Someone has an idea, and goes to the drum company, and says, 'I want a tom-tom this deep.' So the company makes it without doing any research into the way it sounds. Very often, the sound that comes off the bottom head on a power drum is nothing like what drummers think they're getting when they hit the batter head. This company has not only taken note of the research done by the Federal Institute, but it does its own research. If the basic tone of a deep drum is going to be ruined by overtones, Sonor will beef up the shell to counteract it, because Sonor cares about the way its drums sound. As percussion manufacturers, the people at Sonor know that, with a chime bar for instance, it isn't only the note that the bar itself is tuned to that matters, but it is the proportions and material of the sound chamber underneath it which have to project the note accurately. Otherwise, it will sound wrong. All these things are researched and carefully worked out. The same methods are applied in designing drums. The research that has been done, and is still being done, at the Federal Institute wasn't commissioned by Sonor. It is available to everyone, but nobody else has taken it up!"

Oliver Link continued, "We don't want to have a situation where we are telling people that they have to use heavier shells, because it is always the better sound. The reason why we offer so many different shell sizes and combinations of thicknesses is that we want to give the drummer the largest possible choice of sound. Some people want the livelier sound, so we give it to them."

"There is another very important point," Horst Link added, "and that is the bearing edge on the shell. The point at which the head touches the shell is crucial to the sound. It must be absolutely straight, of course, and narrow with as small an amount of shell material touching the head as possible. The type of material used to make the shell is important at this point, too. The difference in sound from shells made of different materials comes mainly from the edge: The harder the edge is, the crisper the sound. So you get a crisp sound from a drum with a metal shell, but you won't get one from a drum made with a soft material. Our drums have got hard, thick shells, but we make sure that the bearing edges are narrow. They are cut at 45 degrees inside and out. Also our shells are slightly smaller than the hoops on the heads, so that the heads 'float,' which means that there is no clogging up of the sound with the hoop rubbing against the shell."

According to Andreas Link, "We used to make thin shells with reinforcing rings top and bottom, but we realize now that there needs to be a free passage of air between the heads on the inside of the shell, and anything close to the heads only serves to block off the sound." Horst Link agrees. "Yes. This point close to the head is where the vibration starts, and if you put an obstacle in the way right next to the head like that . . . ." Andreas Link concluded, "It's the worst thing you can do."

I raised the point about the rims on Sonor drums: I had been led to believe that cast rims were better than the pressed steel variety', particularly when it comes to cutting down overtones, and yet I had only seen cast rims on the Signature snare drums. Steve answered, "You get a choice. The standard pressed rim is 1.5mm thick, but the Signature pressed rim is 2.5mm thick. That helps cut down on the overtones. They cost as much to produce as a cast rim. They are pressed out on the same machine that is used for making the metal snare drums; this means that they are seamless. They are not a cheap option. With a normal pressed rim, you have more flexibility with the tuning. A cast rim is so solid that you can very nearly put one on a 14" drum, put four tension rods on it, and tune it. If you tighten it down in four places, the rim is so rigid that it will pull the head down evenly all the way around. The pressed steel rim won't do that, so you need all the tension bolts to be brought into play to tune the drum. If Sonor uses pressed rims, it isn't for cost; it's for tunability-the customer has a choice anyway-at the same price."

We know that there are quite a few top drummers, like Steve Smith and Jack DeJohnette, who use Sonor, but we don't open Modern Drummer and find advertisements showing pictures of dozens of big names who use the drums. The marketing policy for the world's most expensive drums seems to be much more subtle. Why is this?

According to Oliver Link, "We have never paid a drummer to play Sonor. Other companies actually pay people regularly every month to use their products, but that isn't completely convincing. If you're paying them, they are not doing it from their own free will, are they? The endorsees that we have are convinced ones. They don't switch around very often. They stay with us."

Andreas Link added, "There's a very simple reason: If you make a drum for top drummers, you have got to sell it to top drummers. If you give them to top drummers, who are you going to sell them to?" Oliver Link stated, "We do give a limited number of kits to certain drummers, but they always do something for us in return-clinics, that sort of thing. They don't get kits just because they are 'names,' and they never get money from us. Endorsement policy, as I regard it, is only one part of our marketing strategy. You can't have an endorsement policy without having an advertising policy and a product policy. It is all interconnected. The most important thing is the quality of the product; when people are paying a lot of money, they expect you to maintain good service, good delivery, and so on. You can't afford to compromise on the product or on customer service. But as far as marketing goes, this is where our advantages lie. We can't compete with the cheap kits that are imported from the Far East, and we don't want to. We have to keep the level high, and although it is a hard task, we are succeeding."

According to Steve Gardner, "What we have found is that, if people are prepared to pay a high price for a top-quality drumkit, they are prepared to pay the highest price for the best possible drumkit." Horst Link added, "The most important point for us is the quality, next comes availability, and third, the price. You might ask, 'What can you-a small company with only 195 people-do to compete against the really big drum manufacturers?' But I say that we are more flexible than the big companies. We are faster when it comes to adapting to changes in the market. We can take better individual care of our customers. If customers come here, I, as head of the company, can welcome them. In larger companies, it would be the head of a division. The contact is greater. I personally know most of our customers. We get our orders out to them quickly. We give service and value for money. That's what we are in business for, and that's what keeps us in business."

You may remember-that Sonor advertisements of a few years ago featured what is probably the most expensive and prestigious car in the world. This stopped, because the car company objected to it. If they had known anything about drums, they would probably have featured Sonor drums in their own advertisements and claimed to be the "Sonor" of cars!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Simon Goodwin

It just isn't the sort of setting in which you would expect to find a factory. The village of Aue, near the town of Bad Berleburg in Westphalia, is in one of the most beautiful rural areas of West Germany. The district's main industries are agriculture and tourism, the neighboring hills being very popular with hill walkers. You might imagine that the Sonor factory is out of place and detracts visually from the rustic surroundings, but this isn't the case at all. The plant is a small collection of modern buildings set in fields well away from the road and the rest of the village. As you approach the factory, it seems to be dwarfed by the pine-covered hills behind it, thus blending fairly unobtrusively into the landscape. There is work in progress to build more and extend the amount of factory space, but at the time I visited, there was the main factory building, which also houses the company's administration, the Signature Building where the top-of-the-range drumkits come to be finished and assembled, and Horst Link's original 1946 ex-British Army hut, which is now used for storing educational books, catalogs, etc.

There are 195 people working at the Sonor factory: 155 in production and 40 in administration and distribution. Everything with the Sonor name on it is manufactured here, with the exception of the drumsticks, which come from England, and the magnificently coopered conga and bongo shells, which come from Austria. (The cooper who makes these shells used to work for Sonor at Aue, but he now lives in Austria and supplies the shells as a subcontractor.) Sonor buys a few small components such as screws, threaded bolts, small pressed items, and the rubber feet for stands. Three thousand different raw materials come into the factory, and they are used in the manufacture of 2,000 different parts. As certain parts are used for more than one item, they actually produce 2,800 different finished products. It is part of Sonor's policy to manufacture "in series," in order to ensure that they always have enough manufactured items in stock to meet any orders that come in. This means that they will produce enough of the items that they have to tool up for at any one time, so that the relatively straightforward procedure of assembling them can be done quickly and efficiently on demand. This also means that a customer won't have to wait months, until the next time the production line is making a drumshell of a particular size. The shell can just be taken from stock, covered if necessary, and assembled.

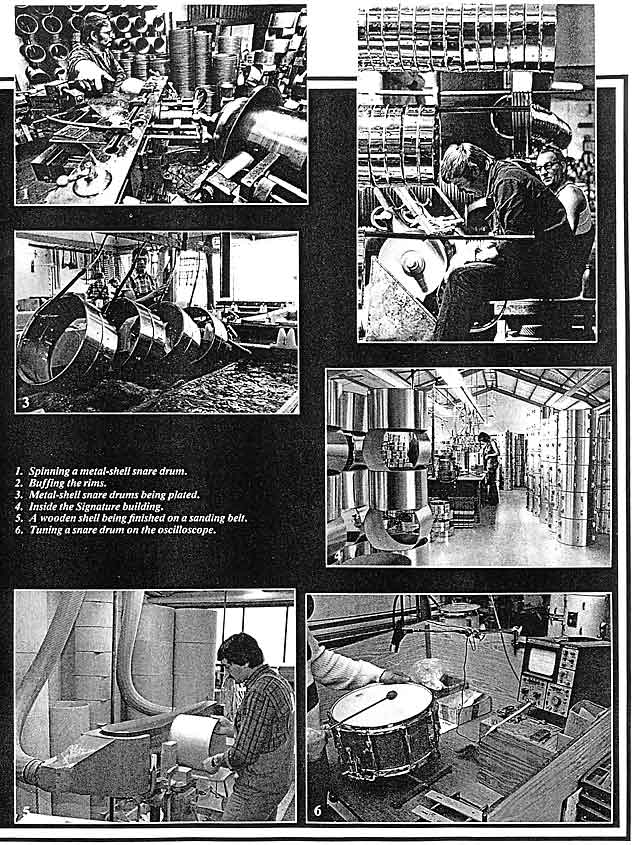

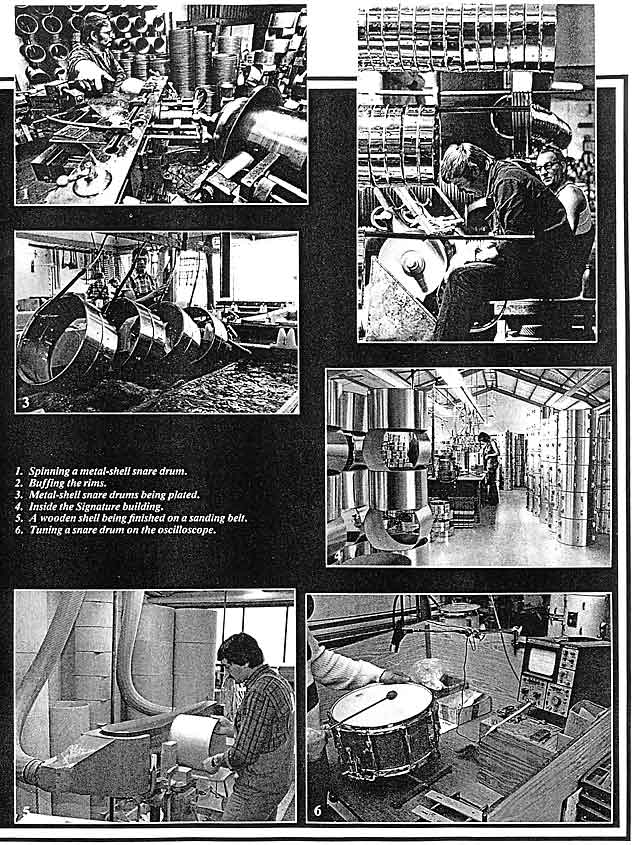

Three people took me around the factory: "Vice-President" Andreas Link, RoIf Lukowitz, who is one of the production managers, and Steve Gardner of Sonor UK. Andreas and Rolf obviously know the factory like the backs of their hands, and Steve has visited it on many occasions, but all three of them displayed a remarkable enthusiasm and pride in everything they showed me. I saw various manufacturing processes that are unique to Sonor and that they described as "our little secrets." After this had happened a few times, I was beginning to get worried. Was I going to have anything to write about, or was I being sworn to secrecy? Steve laughed at this and said, "We don't really mean secrets. Call them special tricks of the trade if you like. We don't have secrets; there's nothing to hide. For instance, we make a seamless metal-shell snare drum; we are proud of this product and pleased to show people how it is made. Other firms claim to make a seamless metal shell, but they won't show you the shell being made. The fact is that they usually buy them in from outside and often there is a join, but you can't see it because it is very cleverly disguised." "You can see it," said Rolf. "If you really know what you're looking for, you can usually see a join if it is there."

Sonor's metal-shell snare drums are actually spun out of large discs of top-quality ferro-manganese steel, which have been manufactured specifically for that purpose. Amazingly, this spinning process is carried out with the metal cold. To heat and then shape the metal can alter the molecular structure and weaken it, but the cold spinning process used by Sonor ensures that the shell is perfectly round and completely consistent in every way. The machine that performs this feat is a large lathe with some fittings that have been developed at the Sonor factory specifically for the job. The ferro-manganese steel disc is spun at great speed against a cylindrical former. As it spins, a flywheel is brought to bear against the side away from the former. As the spinning disc is pressed by the flywheel, it slowly curves and then begins to assume the shape of the former. The flywheel moves slowly along the length of the former, pressing the steel against it and smoothing it down. After about eight minutes, the steel disc has been transformed into something that looks like a bucket with straight, rather than conical, sides. The "bucket" base is then removed, the edges are trimmed and beveled, for some models the bead is pressed around the middle of the shell, and then the drum is ready for the next process, which is the preparation for the plating.

We visited the department in which the metal parts, such as rims and nut boxes, as well as drumshells, all receive individual attention to make sure that they are without blemishes of any kind before they are plated. Andreas said that he used to work there during the school holidays, when he was a boy. "You have to be very careful," he said, indicating a workman sitting very close to the fast-spinning buffing wheel that he was using. There was a row of copper-colored snare drum shells on a rack. I commented that I hadn't seen any like that before and was told that those shells were one-third of the way through the plating process. They had received their first coating, which was copper, and they were going to be polished before going back for the second coating, which was nickel. All chromed parts have a coating of copper and a coating of nickel under the chrome. The drumshells and the larger items are always polished, by hand, between each coat, which is what gives them the excellent high shine.

The plating is done in a series of tanks. There is a special pully system above the tanks, so that the items for plating can be lowered into the tanks, raised out of them, and moved forward without the operator needing to handle them. In addition to the copper, nickel and chrome tanks, there are four tanks that contain cleansing liquids (in two cases clear water). The metal items have to be dust-free and de-magnetized before the plating goes on; they are also washed between the copper and nickel stages, and again between the nickel and the chrome. I saw a collection of small items like wing nuts being plated. These were not removed between each of the plating stages to be polished. Although the whole process takes about two hours, there were items at each stage of the process, so that all stages could be pointed out to me. Small items like these are not lowered into the tanks individually; they are attached to a small "tree" made of rubber that is lowered into the tanks and can be reused. It is interesting that, when the finished chrome comes out, it looks more yellow than silvery. The silver color appears at the final polishing.

Not all metal items are chromed; some are sprayed: chime bars, for instance, and the black hardware on the new Phonic Plus "Hi-Tec" drums. The lacquer is sprayed onto the metal, and then the parts are put into a heat chamber where they are baked at a temperature of 200 degrees C. The finish that is produced in this way is as hard as, if not harder than, plating.

|

|

|

|

On to the wood: We visited the storeroom in which the stacks of wood are kept. Sonor drums are made from two, three, or four layers of three-ply wood, depending on the model. "It is most important," said Andreas, "that we keep control over the quality of the wood. So we buy the wood ourselves before it is made into three ply. We supply our subcontractor with the raw materials for making the plywood, and this way we guarantee the quality." The sheets of ply are stored in a cool room until four days before they are needed for the manufacture of drumshells, at which time they are taken into the much warmer room in which the shells are made.

It is necessary for the wood to have time to become acclimatized to the temperature of the shell room, because when the shells are made, the pieces of ply are pressed together at a high temperature. Wood is sensitive to temperature, and after the ply sections are cut to size, there is no room for error if the ply happens to expand or contract during the process. The inner pieces of ply are cut at an angle to give a diagonal join where the two ends meet. The outer layer is cut straight. The cut sheets are then placed between special rollers that coat them evenly with glue. The sheets that are to become the inside and outside of the drumshell are only coated on one side, while the ones that are to be sandwiched between them are coated on both sides. They are now ready to go into the shell machine. There is a different machine for each diameter of shell size that Sonor makes. The machines are very sophisticated molds, for molding sheets of plywood together. There is a cylindrical outer casing, the inside of which is the same size as the outside of the required drumshell. The plywood sheets are bent by hand, so that they can be placed in the machine in the position in which they are to be pressed together. The outer layer goes in first, so that it rests against the inside of the "mold," then the next layer goes in with the join in a different place, and so on. When all the plywood is in place, an inside former is moved into position on the inside of the shell. This former is not only heated, but is able to expand, thereby pressing the sheets of plywood together against the inside

of the "mold." The drumshell is left under heat and pressure like this for about 12 minutes to allow it to "set." When it is taken out of the machine, the shell is as strong as any wooden shell of a given thickness could possibly be. It is also perfectly round. Each plywood sheet has been stuck, under pressure but free of tension (without being pulled), around the sheet next to it, so there is no overlap of any sheet against itself, and no possibility of the plies being out of true. In the case of wood finishes, the outer ply is the finish. It isn't a piece of veneer that is added on later. "It is all done at once," said RoIf proudly. "That's a specialty of Sonor."

The shells are finished by hand with the help of a sanding belt, and the bearing edges are cut on another of Sonor's special machines. Each shell receives the individual attention of a craftsman, but to ensure an accurate bearing edge, the drum is slowly turned against a revolving cutter, which is set at exactly 45 degrees. As the shell is resting on a flat metal surface during this process, there is no possibility of error. The largest 45-degree cutaway is on the inside of the shell, but it doesn't go straight inwards from the outside edge. There is another 45-degree cutaway on the outside, but this is much nearer to the outside edge. This double cutaway gives a very narrow bearing edge indeed. "Even though our drumshells are very thick," said Steve, "the amount of the head that actually touches the shell is less on our drums than on anybody else's. They are beautiful - the best shells in the world!"

The next stage is the spraying room, in which the shells are sprayed with lacquer. Andreas explained, "The wood finish which you see on our shells is the natural color of the wood. There is no dye added to give an even color. That is in the quality of the wood we use. The clear lacquer coating is to protect the shell's surface and to seal it against moisture." The cream and onyx finishes that are available as alternatives to the Scandinavian birch in the Sonorlite series are also applied in the spraying room, because they are lacquered finishes. These lacquered Sonorlite finishes take longer and are more expensive to produce than plastic coverings, but research has shown that the lacquered finish gives the drumshell a character so close to that of a natural wood finish that the difference in acoustic properties is negligible. These finishes are "highly durable, and resistant to light and fading." Rolf underlined the care that is taken with the lacquering. "There are normally four-sometimes five-coats of lacquer that go on: two undercoats, and two or three top coats. Between each coat, the shell is rubbed down and polished, and before the final coat goes on, it is rubbed down with special, fine, wet sandpaper. Of course, all of this is done by hand, and each shell is carefully checked so that it is visually, as well as acoustically, perfect."

With the exception of the natural red mahogany, the finishes on the Phonic, Phonic Plus, and Performer drums are plastic coverings. Three machines are used at this stage in the process, and each of them is unique to Sonor, but each shell is worked on individually by a craftsman. There is no element of mass production. The shell is first hung on a roller with the covering material on top of it so that the material's underside is facing upwards for gluing. Another roller comes down from above and rolls the covering material along its length. As the material passes beneath the roller, an even covering of glue is deposited on it by the roller. After the material has passed through, the top roller tightens against the drumshell, so that it can be revolved on the roller it is hanging on. As the shell revolves, the top roller deposits an even coating of glue on the shell in its turn. In this way, both shell and covering are glued by the same machine, one after the other. After being left for about 15 minutes to allow the glue to set, the shell is placed on another machine, which actually does five jobs all at once: The covering material is lined up against the shell, the shell is slowly revolved, the material is passed forward and pressed against the shell, and while all this is happening, the covering is being trimmed by "running knives" at either end of the shell. There is a slight overlap of the covering material, which is stuck down by hand, and then the shell is placed on a press, which holds this overlap in place for a few minutes while the glue dries. With the covering stuck all the way around with a complete covering of glue, there is no chance of the

covering "bubbling" in extreme heat or direct sunlight, which can happen with some other drumshells. The surface of the covering material is protected throughout with a layer of something like "cling-film," which is removed later.

Sonor even manages to do something special when it comes to drilling the holes in the drumshells to receive the fittings. Unlike most drums, Sonor's tension brackets don't have lugs that project right through the inside of the shell. The lugs slot into the thickness of the shell about halfway, and the screws come through from the inside of the drum to meet them. This means that they need to have a thicker hole on the outside to take the lug, and a thinner one on the inside to take the screw. This is achieved by having drill bits that have two thicknesses. As the drill goes through from the outside, a thin hole is made all the way through, and then a thicker hole is made part of the way through. For this to be done, the shell is placed in an upright position on a turntable, and the mounted drills pierce it horizontally. Settings are available on the machine for every size of drum that Sonor produces, so that the height of the drills can be adjusted according to the shell size, and the shell is turned the correct amount between hole stations. After this, the drums are ready to be assembled.

The next stage in the production of snare drums seemed, at first sight, to be carrying perfectionism to the point of eccentricity, but Steve was quick to justify it. "You go into most shops where they have a shelf full of different snare drums of different sizes; go along the shelf tapping each one in turn and you will find that they all sound more or less the same, regardless of size and thickness. The reason for this is that the person in the shop has tuned each of those drums to his or her idea of how a drum ought to sound. This means that, in many cases, the drums are not going to be sounding their best. There is no point in having drums with different characteristics if they are all going to be tuned to sound the same. We know, from the research that has been done, what the ideal tuning is for our different models of drums, so we tune them before they are sent out. What the customers do with the drums when they get their hands on them is up to them, but we make sure that the drums leave here sounding right." But do they stay in tune? "Oh yes. With the Snap Lock system on our tension bolts, there is no way they are going to move. The drums stay in tune until the heads begin to stretch after being played for a while; when that happens, they need to be brought up a bit."

The tuning is carried out on a workbench that is specially equipped with a snare drum cradle, mounted in the middle of it so that it can revolve, and an oscilloscope. This is an electronic machine that can be set to be receptive to a specific note. There is a line across a small screen that will show an uneven pattern when the note that the machine hears is wrong. The operator can read the patterns on the screen and judge how to tune the drum to get the even pattern, which indicates the true note. He turns the drum so that each tension bolt, in turn, is under the microphone. Rolf pointed out that, if you want this sort of accurate tuning, this is a very time-effective way of doing it; it takes three or four minutes only, as opposed to half an hour or more if it were being done by ear. As a matter of interest, the drum I saw being tuned was a Sonorlite 71/4 x 14 wooden snare drum. The batter head was tuned to Db and the snare head to Gb.

Eccentric, perhaps. Most drummers just fiddle around with their drums until they get a sound they like, but the scientific research conducted by the people at Sonor has led them to consider the "perfect" sound for their drums-and they don't want anything short of perfection to leave their factory. It is this sort of attention to detail, which one sees at every stage of their production, that makes Sonor what it is. The people at this company are not afraid to say that they make the best drums in the world, and they are not afraid to admit that their drums are the most expensive. The one justifies the other. Sonor's policy would seem to be justified also by the number of drummers who are prepared to ignore trends for particular makes of drums and heavily endorsed advertising campaigns of certain of Sonor's competitors, in order quite simply to go for the best.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This article originally appeared in the August 1985 issue of Modern Drummer Magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|